Turkish baths in Ireland

Glenbrook, Co.Cork

This is a single frame, printer-friendly page taken from Malcolm Shifrin's website

Victorian Turkish Baths: their origin, development, and gradual decline

Visit the original page to see it complete—with images, notes, and chronologies

Victoria Baths and Family Hotel

Dr Curtin's Hydropathic Establishment

The Royal Victoria Monkstown and Passage Baths

The first baths in Glenbrook intended for use by members of the public were opened in August 1838 on the western bank of the River Lee and were known as the Royal Victoria Monkstown and Passage Baths. When first built, they comprised slipper baths, showers, and a cold plunge pool, all of which were luxuriously fitted out.

It was not long before these facilities were augmented by the provision of food and accommodation. Gardens were added, and a variety of outdoor activities were organised to attract and entertain visitors who lived in villages close by.

But the Royal Victoria Baths were not long to remain the only bathing facilities at Glenbrook. Early in 1852, according to local historian Colman O'Mahony (from whose scrupulously researched book The Maritime gateway to Cork much of the information on this page is taken), Dr Timothy Curtin purchased nearby Carrigmahon House together with '13 acres of wooded and landscaped gardens' with the intention of opening a hydropathic establishment in Glenbrook.

Situated 100 ft above the River Lee 'commanding a prospect unsurpassed for beauty' and, like Ireland's first hydropathic establishment at St Ann's Hill, located within a few miles of Cork, the position must have seemed ideal to this well-respected hydropathist and homeopathic doctor.

The hydro

Not much is known about the hydro. Nor, with any certainty, is it known who was its actual owner at various stages of its existence. But its location so close to the Royal Victoria Baths, and what little is known of the relationship between the two establishments, make it of considerable interest.

St Ann's had already been in existence for about nine years and it is possible that Curtin had been on the staff there and that his intentions were known to, and even supported by, Dr Richard Barter, its founder.

Like Barter, and unlike most other hydropathists at that time, Curtin was happy to include vapour baths among the treatments available to his patients. The red stone bathhouse which he added to the original house was designed to include 'six compartments; four for vapour baths, also including cold baths; and two for plunge baths, and a douche.' Although the establishment was not being advertised at this time, 'by July 1852 guests, including some from England, had arrived at Carrigmahon and were paying two guineas per week.'

That enough guests were staying at the hydro to make it financially viable in the absence of any advertising, seems to suggest that good fortune alone was not responsible. A possible scenario, though one for which no evidence has yet been found, is that Dr Barter had advised Curtin on setting up his establishment and was sending him those patients for whom the fees at St Ann's were too high.

Barter was later to follow such a pattern when Turkish baths were opened in Ireland. Many of these were set up with his advice or financial help, or else owned by companies in which he had, for a time, a financial interest. And, as we shall see, after Dr Barter's death, the lease of the land on which Dr Curtin's hydro was built was in the name of a Mr Richard Barter, of St Ann's Hill, Blarney.

The hydro seems to have prospered. Additional land was acquired soon after it opened, and in 1856, the year in which Dr Barter was experimenting with his first Turkish baths at St Ann's, Curtin decided to expand so that additional guests could be housed.

A local campaign was under way around this time aimed at bringing visitors to Glenbrook from farther afield by getting a pier built. This, it was hoped, would encourage travel by steamer from nearby Cork. The campaign was successful and the pier was approved and scheduled to open in 1858.

The hotel

By now the original Royal Victoria Monkstown & Passage Baths had been renamed, were known as the Glenbrook Victoria Hotel and Baths, and were owned by a Mr Robert Watkin Jones who seems to have purchased them some time around 1856. Jones knew that the opening of the pier would be a good time to expand his business and decided to enlarge the hotel and add some new facilities.

At the end of January 1858, a paragraph in the Cork Examiner headed 'The Monkstown Baths, Hotel and Pier' reported that the hotel proprietor intended installing additional bedrooms, private rooms, breakfast rooms, and a commodious dining saloon. And before the start of the bathing season, the report continued, 'Mr Jones is about adding to his establishment that imported luxury of which so much is spoken now-a-days, the Turkish Bath'.

The extension and the new Turkish bath were completed at the beginning of June and an advertisement headed 'Royal Victoria Hotel, European and Turkish Bath, Glenbrook' announced that to mark 'the opening of the new Turkish Baths, Glenbrook Pier, and the new building', a celebratory dinner would be held at the hotel with the Mayor of Cork in the Chair. The cost was to be one guinea and included 'Champagne, Moselle, Madeira, Claret, and Port and Sherry Wine. Dinner, under the supervision of the 'Chef de Cuisine' Mr B G Martin, would commence at 6.30 sharp, and afterwards a special train would leave for Cork at 11 o'clock.

The dinner, at which Dr Barter was present, was held on 9 June and was reported at length in the Cork Examiner later in the week. The report included full details of the sumptuous menu enjoyed by about eighty (male) guests, about half of whom were named.

The Mayor proposed a toast to the success of the hotel 'with its novel addition of the Turkish bath', alluding to the 'great spirit and enterprise which the proprietor had shown in carrying out his undertaking'. At the Mayor's request Dr Barter 'acknowledged the sentiment, so far as regarded the Turkish bath'.

Barter had known about the building of Jones's Turkish bath from the beginning and was initially pleased to see how Turkish baths were spreading round Ireland. He wrote to his friend Mr Wrenfordsley in February, shortly after the Cork Examiner had announced the proposed extensions and additions to the hotel, 'The Turkish Bath prospers in the South [of Ireland]. There is more building at the Monkstown Ballis, near Cork, and I have just completed an additional Bath on my grounds.'

But Barter's comments of approbation at the dinner, as reported by the Cork Examiner , seem less than wholeheartedly enthusiastic. 'It needed but the carrying out of a few alterations such as he could suggest, to enable it to give much greater accommodation, and become much more profitable to the owner.' In fact, Barter had a number of other concerns which only became apparent some years later.

But to less knowledgeable critics, the design of the Turkish bath, with its 'stained dome lights, crimson hangings, a central fountain, richly tesselated floors and handsome couches', matched the standard set by the marble fitments of the original baths and was in no way inferior to them.

According to an early advertisement in the Cork Examiner, guests could stay at the hotel for two guineas per week—the same rate as that obtaining at the hydro—and this included the use of the hot, vapour, plunge and shower baths. But the use of the Turkish bath cost an additional 2/6 per week.

For those on a day visit to the baths, admission charges varied according to which facilities were used. A Turkish bath cost 2/- on its own, or 3/- with a return ticket for rail and boat travel from Cork.

Dr Curtin adds Turkish baths to the hydro

Meanwhile, a short distance further away from the river, Dr Curtin seems rather belatedly to have recognised his missed opportunity to be the first with a Turkish bath. Galvanised by the thought of all the publicity likely to result from Jones's celebratory dinner, he determined that damage limitation was called for. Somehow he managed to get an article published in the Cork Examiner—only marginally shorter than the one describing Jones's celebratory dinner, and on the very same page of the newspaper. Curtin's article described the new Turkish bath then in the process of being built at the hydro and which was 'very far advanced, and will in all probability be completed, and in working order, in about three weeks from this'.

Whether this was ever a real possibility (which was in the event delayed), or an acceptable commercial exaggeration, we may never know; the description of Curtin's forthcoming bath was clearly (what we should now call) a spoiler designed to diminish the impact of Jones's publicity.

In fact his Turkish baths were not opened until some time in the autumn. They seem to have been built in stages, each area being opened as it was completed. And not until eleven months later, in May 1859, did the Examiner carry an advertisement mentioning that Dr Curtin's hydropathic baths included 'an elegantly constructed Turkish Bath, now in constant use'.

The description we have of it was largely written before the bath was finished and it is not known whether it was completed as planned, or whether changes were made during the course of construction. But it is probably fair to assume that the bath was broadly similar to the one described in the spoiler article which appeared in the Examiner.

Cautiously designed on similar principles to others already in existence, the bath was decorated in a less flamboyant style than the one at the nearby hotel.

It comprised two main hot rooms and what were, in effect, two cooling- rooms. The actual cooling-room was partitioned into areas 'of such dimensions as to allow cosy knots of three or four to enjoy their friendly and familiar chat without the presence of a crowd.' The second seems to have been a smaller cooling-room, unusually without any of the furniture or fitments normally associated with such a room, and 'reserved merely for the purposes of temporary cooling, in the case of persons who might feel inclined to do so while undergoing the bath, either as a matter of pleasure, or through inability to bear the continuous heat.'

Each of the two hot rooms was about fourteen foot square and was surmounted by an octagonal dome about nine foot high making for a comfortable airy atmosphere. At the centre of the tepid room was a fountain surrounded by seating which also formed an octagonal shape, while around the walls were couches for those who preferred to recline. A douche room, with showers at various temperatures and pressures, led off the tepid room.

At the centre of the hot room, was a shampooing slab instead of a fountain. The heating apparatus, normally placed close to the hottest room in a Turkish bath, was here placed midway between the two rooms, a set of dampers being used to regulate the temperature of each. The report claimed that such a system was said to be Curtin's own idea, but there is no evidence to support this.

If the facilities at Carrigmahon House were simpler than those at the hotel, the Turkish bath (with its lower level bathing pool), was only one of a series of therapies available at a hydropathic establishment rather than a luxury designed for those staying at a hotel or to attract day visitors to Glenbrook.

Hotel fire and reconstruction

However, Curtin had the field to himself for two years after 11 July 1859 when a fire destroyed the Glenbrook Hotel's north wing and the Turkish bath.

This must have been a considerable setback for Jones because the fire occurred just at the time when Glenbrook was at its most popular, a popularity which was to be short-lived as nearby Crosshaven grew in popularity after it too built a steamer pier of its own.

It took two years, and an advance of £700 towards reconstruction costs from the Cork Blackstock and Passage Railway Company, for the rebuilding to be completed. And the new Turkish bath was quite different, both from the one it replaced and from the one at the hydro.

Barter vs. Jones

During the period when the new bath was being planned and built, a major controversy arose in the Irish press about whether the hot air in a Turkish bath should be dry or humid. It started in the pages of the Dublin Hospital Gazette and was taken up the following day in the Cork Daily Herald.

The details of the controversy can be found elsewhere on this site; suffice it to say here that there was much (unwarranted, but widely published) criticism of Dr Barter's Turkish baths, especially the one which the critics called the establishment at B*** (ie, Bray).

One of the main arguments of Barter's opponents, Drs Corrigan and Madden, was that hot air without vapour was harmful to bathers, an argument for which no specific evidence was given by its proponents. They went on to suggest that in calling his baths 'Improved Turkish baths', Barter was attempting to hoodwink the public into thinking they were the same as the Islamic hammams found in Turkey which were, they stated, properly humid and, therefore, healthy to use.

In due course these arguments were fully answered by Barter and his supporters, and his 'improved' Turkish baths continued to prosper.

But to Robert Watkin Jones, a non-medical entrepreneur, it must have seemed an attractive idea to replace the bath which burned down with one which he could claim was, according to these two respected doctors, a genuine Turkish bath.

So far as its external appearance was concerned, he seems to have created the desired effect. Local historian Charles Bernard Gibson wrote,

The Hotel and Baths of Glenbrook stand midway between Passage and Monkstown. Viewed from the river, they remind the traveller of a Turkish temple on the Bosphorus.

Hardly—though the author might be forgiven some artistic licence. Our current post-Said views on orientalism have accustomed us to such 19th century writing. And while the Irish painter John E Bosanquet was no Ingres, he too seems guilty of a certain romanticism in his painting of the hotel.

When the new bath at the hotel was opened in July 1861, it was advertised as 'THE ORIENTAL HAMAAM, OR REAL TURKISH BATH'. It was, the ad continued, 'The only one of its kind in the United Kingdom, and admitted by the admirers of the "Improved Turkish Bath" to be infinitely superior to it in all the most essential points…'

Hammams in Turkey—and elsewhere in Islamic communities—are humid, and often steamy, because Muslims are in the habit of washing themselves there before prayers are said. The humidity is not purposely created for health reasons (or any other reason) but is an inevitable consequence of the use of water for washing within the hot rooms.

Jones, on the other hand, introduced steam artificially into his hot room because Drs Madden and Corrigan had suggested that this was healthier. A consequence of this—made into a selling point by Jones—was that in a steamy atmosphere perspiration was produced at lower temperatures than in a conventional hot room such as those to be found in Dr Barter's establishments. This totally ignored the fact that Barter originally went to great pains to ensure that the hot air was dry in order to reach those higher temperatures deemed necessary for use as an effective therapeutic agent.

Jones arranged a complicated series of dampers, taps, and flues running between an upper and lower floor to deliver adjustable quantities of hot air at appropriate temperatures through one flue, and steam-heated vapour through the second. This system was the main feature of a patent which Jones applied for on 26 August 1861 for 'Improvements in heating and ventilation, especially applicable to Turkish Baths'.

In some ways his introduction of a steam flue was a precursor of the ubiquitous prefabricated steam room found in modern health clubs, but it was definitely not a Victorian Turkish bath and seems to have had a fairly short life.

Jones announced his retirement just over a year after the new bath opened. This seems strange so soon after his investment in the new bath and the effort involved in a patent application. Perhaps he discovered that there were problems with his new heating system and that it required constant repairs, or perhaps he foresaw the coming decline in the popularity of Glenbrook. But for whatever reason, the hotel was soon up for sale. It was bought by a new Glenbrook Hotel and Bath Company which announced ambitious plans for its development. However, these came to naught and the hotel was on the market again three years later.

Given the complications of the heating and ventilation system, it seems most probable that the Turkish bath closed when Jones retired. Some support for this theory may be gleaned from the advertisement in the Irish Times in 1869 which offered the hotel for sale 'with a Turkish bath'—no mention here of 'Hotel and Oriental Hamaam', or of 'The only one of its kind in the United Kingdom'. Anyone in the market for such a well-known property would be forgiven for assuming that while the hotel was being sold as a going concern, the Turkish bath was not. And when the hotel was again put up for sale in 1883 by James Coughlan, who had by then owned it for some time, there was no mention at all of a Turkish bath, but only of hot and cold baths.

Evidence of a more concrete nature exists to indicate that the Turkish bath closed some time before then. For, on 7 November 1868, the Irish Times published an important Letter to the Editor from Dr Barter which tells us much about Jones and his Turkish baths.

On the previous Wednesday, 4 November, the paper had published an anonymous review of Durham Dunlop's Air and water in health and diseases. In it, the reviewer had claimed that 'a Mr Jones, of Glenbrook, Passage' had been the first to erect the true Turkish bath in Ireland. This must have been too much for Barter to allow to go unchallenged. Not only was Barter universally recognised as the father of the Turkish bath in Ireland, but Jones had actually espoused the very type of humid bath which Barter and Urquhart had rejected as being unsuitable for use as a therapeutic agent.

In his letter, Barter stated categorically that he had 'erected the first Turkish Baths in Ireland here [ie, at St Ann's Hydro], under Mr Urquhart's directions, in 1852.' This was not actually so, and it is not clear why Barter wrote 1852 (instead of 1856) as the year in question; it may have been a misprint, or a failure of memory in the heat of the moment. Barter would never knowingly have claimed an earlier date than was the case. In any event, his claim to have introduced the Turkish bath to Ireland was not invalidated even by a four year difference. This could easily be checked because, as the letter continued, 'A full report of the ceremony of laying the foundation of it was published in all the public papers of the time.'

This much is already known by all who are familiar with the history of the Victorian Turkish bath in Ireland, but the next part of Barter's letter was more revealing. Describing the first bath he built at St Ann's, he wrote that it,

was charged with vapour according with the true Eastern Baths; but, I was soon obliged to abandon the visible vapour. This [vapourless] bath became such a favourite that large as it was, I had, a couple of years after, to build a second one here. A Mr Martin, a brother-in-law of the Mr Jones in question [and 'Chef de Cuisine' at the ceremonial dinner marking the opening of his original Turkish bath], was my house steward at the time, and he studied the structure of this building. Shortly after this, he left my employment to build a bath for Mr Jones, and in accordance with the published opinion expressed by a high medical authority which I need not name, he added to his bath a steam pipe from the furnace, which he and his friends considered an improvement, but which I believed to be the reverse, as it made the baths feel stuffy, interfered with the cooling effect of evaporation from the skin, made the baths very disagreeable and highly dangerous. Mr Jones's bath is long since closed, as are all the baths erected after his model, while the baths on my principles are extending rapidly over Western Europe and America. I think, then, I may fairly claim to be the person who has established the bath in Western Europe, and which has become an Irish institution.

Dr Curtin's hydro and Dr Barter: a connection?

With less controversy, the Turkish bath at Dr Curtin's Hydropathic Establishment continued in typical low key manner and was well-respected, according to Charles Bernard Gibson who, in 1861, noted that,

CarrigMahon is a noble mansion, and commands a splendid prospect. Here we have the Turkish baths in perfection, and the hydropathic system, conducted with ability and professional skill, by the proprietor, T Curtin, Esq, MD

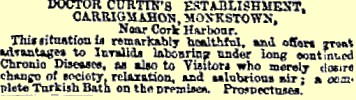

And Curtin's straightforward advertisements contrasted sharply with the extravagances of Jones's 'oriental hamaam'.

Advertisement from the Irish Times (7 July 1865) p.2

According to Colman O'Mahony, Curtin's Hydropathic Establishment continued for a short while after Curtin's death in 1876.

This leaves unanswered, for further research, the question of who was the proprietor of Dr Curtin's establishment after his death. Dr Barter had already died six years before Curtin, but could it have been his son Mr Richard Barter? Clearly the management of the hydro had been in Curtin's hands since its foundation, but could Richard or his father have actually owned it for some time before Curtin's death? Could Dr Barter have been the proprietor of the hydro from the time of the installation of its Turkish bath, or even earlier?

What we do know is that in 1879 it was 'intended to erect sixteen blocks of first class houses at Carrigmahon' designed by the architect, Mr Kearns Deane Roche; that to facilitate this, 'Mr. Richard Barter, of St. Ann's, has recently made arrangements with Lord De Vesci for an extension of his lease'; and that by 1881 Roche had revamped the scheme to comprise nine semi-detached 'Carrigmahon Villas'. These were to be built on a site about which the Irish Builder wrote that 'it need only be mentioned here that for many years before this charming spot, Carrigmahon, passed into the hands of its present proprietor it was far famed as a hydropathic establishment, conducted by the late Dr Curtin.'

One of the villas was destroyed by fire in 1913; the others were demolished shortly afterwards.

Marcia D'Alton

Marie Gethins, for information about Bosanquet's painting, and much else

Chapter 9 of Colman O'Mahony's The Maritime gateway to Cork has been indispensable

Crawford Municipal Art Gallery, Cork, for permission to reproduce Bosanquet's painting

Photograph of the hotel and baths courtesy of the National Library of Ireland

The original page includes one or more

enlargeable thumbnail images.

Any enlarged images, listed and linked below, can also be printed.

The baths in August 1849

The Royal Victoria Hotel, 1858

Advertisement in the Cork Examiner

Detail from 'Glenbrook and Turkish baths'

Advertisement for the rebuilt Turkish baths

Patent application by Robert Watkin Jones

Royal Victoria Hotel and baths, after closure of Turkish baths

Victorian Turkish Baths: their origin, development, and gradual decline

Comments and queries are most welcome and can be sent to:

malcolm@victorianturkishbath.org

The right of Malcolm Shifrin to be identified as the author of this work

has been asserted by him

in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

© Malcolm Shifrin, 1991-2023