Turkish baths in provincial England

Salisbury: Queen Street (16)

This is a single frame, printer-friendly page taken from Malcolm Shifrin's website

Victorian Turkish Baths: their origin, development, and gradual decline

Visit the original page to see it complete—with images, notes, and chronologies

Salisbury Turkish Baths

The first Turkish baths

On the afternoon of 27 December 1874, 'in the unavoidable absence of the Mayor' of Salisbury, the Ex-Mayor, Mr J W Lovibond, welcomed a small group of 'gentlemen who have taken an interest' in the project, to the official opening of the Salisbury Turkish Baths. Built on part of the site of the Plume of Feathers Inn for their proprietor John May Jenkins, they were reckoned to be 'as well appointed as any in the provinces.'

Three hot rooms, maintained at 130°F, 170°F, and 230°F, and a shampooing room, all led off the cooling-room located on the first floor of the building. Additionally, there were hot baths and a range of spray, wave, and rose showers which could also be used by those not wishing to have a Turkish bath, and by those separately attending for hydropathic treatment or massage.

But although we know what facilities were provided, and that they were located on two storeys accessed by a fine, much earlier wooden staircase, we do not know their exact layout.

All we know for certain is that the baths, at No.16 Queen Street, were at the north-east corner of Cross Keys Chequer, with an entrance in Plume of Feathers Yard, which was accessed through a narrow passageway from the street.

Special hours were set aside for women bathers on Mondays and Thursdays, supervised by the wife of the Manager, Mr James Stockholm of London. Unusually, perhaps copying the Jermyn Street Hammam, a specialist, Mr Tubar, was employed to provide coffee 'after the Turkish, French, and English fashions.'

During the opening ceremony, one of the speakers, Mr W Pinckney, a local banker, thanked Mr Jenkins for his public spirit in opening such a bath in Salisbury. Jenkins replied that when he originally considered the undertaking, he had offered to build and provide the baths if twenty subscribers would each guarantee to take five pounds worth of tickets in the first year. Twenty-five gentlemen agreed, and he had no doubt that the baths would, therefore, be successful. Only twenty-four of these were named in an early advertisement for the baths, so it seems that one guarantor might have dropped out.

Further advertisements that year were mainly limited to stating the bath's opening hours, and including a few testimonials praising their efficacy. All appeared to be going according to plan, but early in the morning of 1 February 1881, barely thirteen months after their opening, fire broke out in the furnace room. By the time the fire brigade arrived the roof had been destroyed and, when the blaze had finally been extinguished, the baths 'with the exception of the cooling-room, had been entirely destroyed or irretrievably damaged.' The premises were old, mainly built of wood, and so were easy fodder for the fire. Fortunately, Jenkins was fully insured for the building and, separately, for its contents. And, miraculously, the fine old wooden staircase was spared.

The second Turkish baths

By the last week of July, the baths had been rebuilt to a new design. The speed with which they reopened may well have been helped by the fact that Mr Jenkins was himself a plumber and also owned an ironmongery establishment in the same building.

There were several improvements, including the widening of the main entrance and the repositioning of the smoking room. But the most popular improvement would have been the addition of a large plunge pool.

Although, again, we do not know the exact layout of the baths, we can identify a few of its features from a plan of the first floor of the building, drawn as part of the survey conducted before the baths were demolished in 1974.

Here, the wooden stairs leading up to the baths, and the unmistakable top-lit octagonal cooling-room can easily be identified. But where the limits of the baths were, and what facilities were located on the ground floor, is still unknown.

Some time after the baths reopened, Henry James Ponter and his wife Mary, were appointed Manager and Manageress. It may be that they were responsible for making the profitable arrangement whereby Salisbury Infirmary sent out some of their patients for Turkish baths, rather than building their own as, for example, the infirmaries at Newcastle-on-Tyne and Huddersfield had done in 1860 and 1876.

It is not known when this practice started, but in 1890 the baths received 12 patients. By 1893 the number had risen to 49, and the following year—the last for which figures have been found—141 patients made use of the Turkish baths. This must have been good for the reputation of the baths with the general public.

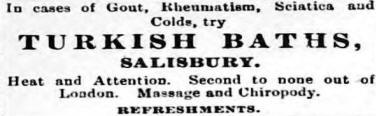

At the beginning of 1898 vapour baths were installed and the establishment was being advertised as The Salisbury Turkish and Russian Baths. But this was short-lived, and by the following year advertisements had reverted to simply calling them Turkish Baths. Nevertheless, it was specifically stated that vapour baths, hot and cold water baths, and cold plunge baths were also available.

John May Jenkins died in June 1901, and he was so well thought of by the community that,

As a mark of respect to the deceased and the bereaved family nearly all the tradesmen whose places of business were passed en route to the cemetery had shuttered their windows and a large number of them attended the obsequies at the graveside.

The baths remained closed until 1 August when Mr Ponter, as Manager, presumably at the request of the Jenkins family, reopened them. But Ponter may already have been in the midst of negotiating their purchase, because by the beginning of the new year Ponter had, in fact, taken over the proprietorship of the baths, reduced the prices, and altered the hours 'to suit all classes.'

He made two immediate changes. The first instituted a much lower price, 1/- instead of 2/6d, on two evenings in the week. The second changed the two women's half-days into a single whole day. The first would have increased his income, and the second decreased his costs.

Some time between 1903 and 1905 Ponter ceased to own the baths. The new proprietor was a Mr E A Jenkins, who may have been a son or younger brother of the original proprietor. However, an advertisement of the time gave no indication of who was then managing the baths; nor was there mention any longer of a women's day.

By 1907, Mr G Thomas had become the new manager, though he may have been appointed earlier, when E A Jenkins first took over the baths.

Jenwas still proprietor in the middle of November 1912 when it was announced that the baths were 'Closed temporarily for repairs.' But they never reopened, and the building was demolished in 1974. Rather more happily, the 17th century staircase remains, and has now been incorporated in the Cross Keys Shopping Centre.

This page first published 7 January 2021

David Lovell for permission to use his fine photo of the staircase

Frogg Moody for much information and some very helpful images

Peter Roberts for his interest in the baths and helpful references

The original page includes one or more

enlargeable thumbnail images.

Any enlarged images, listed and linked below, can also be printed.

First floor plan of the second baths

Victorian Turkish Baths: their origin, development, and gradual decline

Comments and queries are most welcome and can be sent to:

malcolm@victorianturkishbath.org

The right of Malcolm Shifrin to be identified as the author of this work

has been asserted by him

in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

© Malcolm Shifrin, 1991-2023