'Semi-success' in London:

David Urquhart, the London Hammam, and

the London & Provincial Turkish Bath Co Ltd

This is a single frame, printer-friendly page taken from Malcolm Shifrin's website

Victorian Turkish Baths: their origin, development, and gradual decline

Visit the original page to see it in its context and with any included images or notes

This is a slightly extended version of the paper given

on 10 July 2003 at the

Monuments and Dust Conference on Victorian London

at Regent's College, London

1: Introduction

When David Urquhart died in 1877 , The Times wrote,

Whatever may be thought of his political idées fixes, he has, at least conferred one great boon upon England in the introduction among us of the Turkish bath, the one Turkish institution which it is certainly desirable to adopt.

When historians attempt to sum up the life of this idiosyncratic, charismatic, idealistic, but in the main forgotten, politician, this is almost the only positive view agreed by all.

Yet in the active years of his political life he was rarely out of the news—a nineteenth century practitioner of pressure group manipulation—warning, to an obsessive degree, of what he saw as the imminent Russian threat to European peace, while eccentrically attempting to have Palmerston impeached as a traitor to his country.

| David Urquhart 1805-1877 | |

| 1831-1837 | Served in the British Embassy in Constantinople |

| 1847-1852 | MP for Stafford |

| 1853-1864 | Main period of activity with his Foreign Affairs Committees and the Turkish Bath Movement |

| 1864-1877 | Retired to Geneva, Switzerland, but continued writing and campaigning for diplomatic openness and morality in politics |

To promulgate his ideas he set up a series of workingmen’s Foreign Affairs Committees whose members organised public meetings, and wrote letters to newspapers and Members of Parliament, attempting to influence public opinion and promote a more pro-Turkish foreign policy.

This is not the place to examine Urquhart’s political views, or try to assess whether such a concentrated political effort had any lasting effect. But it is worth noting, as Asa Briggs was one of the first to point out, that his creation of the committees, his political education of their members, and the loyalty they showed him, were remarkable by any standard.

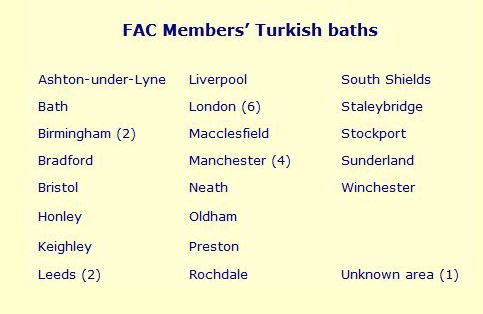

There were, at one stage, over a hundred committees, though many comprised only a handful of active members. The greatest concentrations were in the north and the midlands and all were organized, on a day-to-day basis, by Urquhart’s highly intelligent and capable wife Harriet, together with two or three of his closest friends and associates.

To his contemporaries, Urquhart was the quintessential guru of the so-called Turkish bath—a bath in which the bather sweated in a series of rooms heated by hot dry air, each room being successively hotter than the previous one. In fact, the bath was not intrinsically Turkish, but a humid, watered down version of the ancient Roman thermae.

Urquhart returned from consular service in Constantinople in 1837, but it wasn’t until around 1850 that he started the campaign which eventually led to the opening of the first hot-air baths to be built in the British Isles since the Roman occupation.

The foreign affairs committees became the nucleus of a Turkish Bath Movement, bringing members up-to-date on any new developments. Urquhart wanted each committee to open a Turkish bath, not only to spread a sympathetic understanding of what was perceived as Turkish culture, not only to provide cleansing facilities for working-class people without easy access to running water, but also to support committee members financially, enabling them to become more politically active than was practical in their existing workplaces.

The cause of the bath was also promulgated in Urquhart’s political paper, The Free Press, which published progress reports on the experimental baths being built by Dr Richard Barter and himself at St Anne’s Hydropathic Establishment in Ireland.

With local committee members, Urquhart addressed public meetings about the bath, offering advice and support across the country. Under his guidance, with his help, and sometimes also his financial support, over thirty-five Turkish baths were set up by foreign affairs committees, or by one or more of their members.

These included a co-operative bath at Rochdale, where some of the Rochdale Pioneers also belonged to the Rochdale foreign affairs committee.

In less than a decade, as a result of Barter’s influence in Ireland and Urquhart’s on the mainland, there were Turkish baths in most of the main towns of the British Isles, and in many smaller ones besides.

Urquhart’s influence spread to countries within the Empire, with Turkish baths in Victorian cites such as Victoria in Canada and Melbourne in Australia. The first in Sydney was also the first in Australia, and opened even before London had one. This was the establishment in Spring Street, opened as early as 1859 by Dr John Le Gay Brereton.

These baths had a direct link with David Urquhart, even though Urquhart's own Jermyn Street Hammam was not opened until 1862. For Brereton had, for a while in 1858, acted as visiting physician at the Leeds Road Turkish Baths set up in Bradford by the Bradford foreign affairs committee 'under the advice and direction of Mr Urquhart'. And on 10 July 1860, shortly after his arrival in Australia, he had written to Urquhart to ask his advice 'as our one true leader' in the 'Movement' for the restoration of the Turkish bath.

Urquhart’s influence extended even to an ex-colony when, on 6 October 1862, Dr Charles Sheppard opened the first Victorian Turkish bath in America at 63, Columbia Street, Brooklyn Heights, New York, to be followed two years later by Drs Miller, Wood & Co who opened what was probably the first Turkish bath in Manhattan at 13 Laight Street.

The most obvious sign of Urquhart's success was generally considered to be his involvement in the setting up of the London & Provincial Turkish Bath Company, the joint stock company which owned the London Hammam at 76 Jermyn Street, the excellence and authenticity of which were recognised even in Constantinople.

Success enough, surely?

Yet in his epitome of nineteenth century British history, The Victorians, A N Wilson writes of Urquhart’s Turkish Bath Movement only that he campaigned (semi-successfully) for the re-introduction of the Turkish bath in England.

Wilson’s copious notes include none relating directly to Urquhart. That and, it has to be said, the existence of a couple of unchecked chronological errors, seem to suggest that Wilson has not gone into Urquhart’s Turkish bath work to any great extent.

Is Wilson’s parenthetical ‘semi-successfully’ just a throwaway comment, or is Wilson implying that Urquhart was even less successful than is generally recognised? To attempt an answer, we need to consider not just tangible achievements, but whether Urquhart achieved his own objectives.

This page revised and reformatted 02 January 2023

The original page includes one or more

enlargeable thumbnail images.

Any enlarged images, listed and linked below, can also be printed.

Betowelled patron of the London Hammam

David Urquhart, aged about 69

Harriet Fortescue, wife of David Urquhart

Plan of the Turkish baths at the Old Kent Road Baths, Camberwell

Part of a letter from Joseph Foden, 9 June 1860

The Free Press, 26 May 1858

St Ann's Hydropathic Establishment, Blarney, c.1910

Charles Bartholomew's Bristol Establishment

Bray Turkish Bath, Quinsborough Road

Turkish bath in Sydney, Australia, c.1862

Hotel Victoria, Quebec City, Canada

Ladies' day in the tepidarium: Lonsdale Street, Melbourne, Australia, 1862

Victorian Turkish Baths: their origin, development, and gradual decline

Comments and queries are most welcome and can be sent to:

malcolm@victorianturkishbath.org

The right of Malcolm Shifrin to be identified as the author of this work

has been asserted by him

in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

© Malcolm Shifrin, 1991-2023