Clean in body and mind:

David Urquhart’s Foreign Affairs Committees

and the Victorian Turkish Bath Movement

This is a single frame, printer-friendly page taken from Malcolm Shifrin's website

Victorian Turkish Baths: their origin, development, and gradual decline

Visit the original page to see it in its context and with any included images or notes

4: The committees and their Turkish baths

In 1857, the Manchester Foreign Affairs Committee, with Urquhart’s financial help, built the first Turkish bath in England to open to the public since Roman times. It was managed, and later owned, by committeeman William Potter at his home in Broughton Lane.

It seems to have opened some time around 12 July and Elizabeth Potter, his wife, supervised separate sessions for women, it being always understood that Turkish baths were just as beneficial for women as for men.

Although in Ireland it was Richard Barter who built the first Turkish baths, in England they sprouted as shoots from the various Foreign Affairs Committees spreading rapidly throughout the north and midlands. Their success was due almost entirely to the activities of the vibrant Turkish Bath Movement, and the speed with which it communicated news from committee to committee, directly by post, and nationally by means of their newspapers.

Turkish baths were promulgated in exactly the same way as Urquhart’s political views: by writing letters to local and national newspapers, and by organising public meetings.

Potter’s success fed the committee grapevine and, eighteen months later, at the end of 1859, there were nine Turkish baths in England so far identified as being owned by Foreign Affairs Committees or their members—though there was none, as yet, in London.

That had to wait for another committee member, Roger Evans.

Evans determined to build a Turkish bath at his house in Bell Street, and at the beginning of July 1860, he opened it for use by fellow mechanics at a charge of a shilling a time.

The hot room was heated by a brick flue, about three feet high and nine inches wide, running along three sides of the room, and raising its temperature to 160 degrees Fahrenheit.

Evans’s bath was visited on a number of occasions by R H Goolden, a doctor at St Thomas’s Hospital, who was campaigning to instal a Turkish bath there. Writing in The Lancet, he said,

For some time I watched the effect of the bath in Bell-street, before the establishment of many edifices, so much more complete, which have since been established; and I went into the bath at such times as that I could observe its effects upon the lower classes, who resorted there in great numbers, not as a luxury, but as a remedy, as they supposed, for disease; and I consider, however much anyone may sneer at my occupation, I could not be better engaged than amongst these people, and studying so interesting a subject, even at some inconvenience. There were often ten people in the hot room at one time, all invalids, and I found them quite willing to tell me all their complaints, and to let me examine them. They were principally artizans, small shop-keepers, policemen, admitted at a small fee. I saw there cases of fever, scarlatina, phthisis, gout, rheumatism (acute and chronic), sciatica and tic douloureux, periosteal nodes, bronchitis, pleurisy; forms of skin disease—viz, eczema, psoriasis, lepra, impetigo; diseased liver, dyspepsia, ague, dropsy, with diseased heart and diseased kidneys.

After listing their complaints, he continued,

To expect a cure, or even benefit, in all these cases, would be unreasonable; but I found relief produced to a far greater extent than I was prepared for. The most marked relief was found in cases of gout, rheumatism, periosteal nodes, and sciatica...

This bath was so successful that by 11 September Evans had already built and opened a larger establishment at Golden Square.

This was managed by John Johnson who had served on both the Stafford and Manchester Foreign Affairs Committees and was later to manage Urquhart’s famous London Hammam in Jermyn Street.

6,000 bathers took Turkish baths in the Golden Square bath during its first five months, and income and expenditure accounts were copied and sent to Urquhart for his information.

By the end of 1860, at least two further establishments had opened in London, and in 1896 there were 36.

Altogether, more than one hundred are known to have opened since 1860 though, in August 2016, only four remain, none of which is Victorian.

Throughout the British Isles as a whole, over 600 Turkish baths have been identified, of which only twelve remain in August 2016, five of which are Victorian.

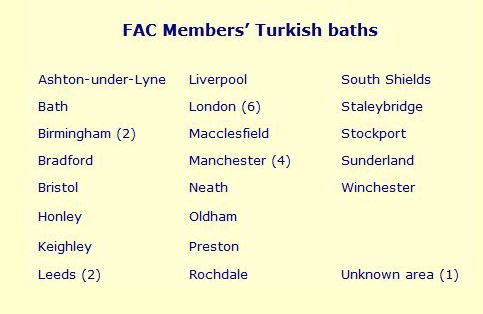

By any standards, the achievement of the committees was remarkable. At least 35 Turkish baths were built by their members for public use.

Urquhart believed that running Turkish baths would help his committeemen financially, free more time for their political work, and give them a base from which to run their committees, with rooms for their public meetings.

So although he believed that baths should be available to the working-class at an affordable price, he did not believe they should be free.

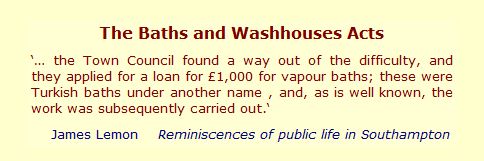

When the first Baths and Wash-houses Acts were passed in 1846 and 1847, Turkish baths did not exist in this country. Consequently, the Acts were widely interpreted, almost certainly incorrectly, to mean that such baths could not legally be provided by local authorities, and therefore none was built in London during the Victorian period.

But outside the Capital, local politicians were more canny.

Southampton Corporation, for example, provided Turkish baths by the simple expedient of calling them vapour baths—which were permitted.

However, there was a downside to this ruse: under the Acts they had to provide First and Second Class Baths, just as they were legally bound to provide two classes of swimming pool.

This page revised and reformatted 02 January 2023

The original page includes one or more

enlargeable thumbnail images.

Any enlarged images, listed and linked below, can also be printed.

First display advertisement for a Turkish bath?

Income and expenditure account for Golden Square Turkish bath

Letter on Turkish Treaty with a plan of Stockport Turkish bath

Victorian Turkish Baths: their origin, development, and gradual decline

Comments and queries are most welcome and can be sent to:

malcolm@victorianturkishbath.org

The right of Malcolm Shifrin to be identified as the author of this work

has been asserted by him

in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

© Malcolm Shifrin, 1991-2023