This is a single frame, printer-friendly page taken from Malcolm Shifrin's website

Victorian Turkish Baths: their origin, development, and gradual decline

Visit the original page to see it complete—with images, notes, and chronologies

This is a slightly expanded version

of a paper given at the

British Association for Victorian Studies

conference on

Victorian cultural industries and elites

at the University of Salford

on Saturday 1 September 2007

1. Introduction

This paper looks at the Victorians’ provision of Turkish baths for their animals, by those who believed that a bath, therapeutically beneficial to humans, should likewise be therapeutically beneficial to animals.

‘Therapeutically beneficial’ here needs some qualification. In 1858, William Potter's Turkish bath in Broughton Lane, Manchester—the first Victorian Turkish bath in England, opened only a few months earlier—was already claiming that it would cure, inter alia, colds, influenza, gout, rheumatism, consumption, and liver disorders. Soon, other bath owners were claiming it could cure anything from toothache to syphilis.

Clearly this last claim was nonsense, while others were greatly exaggerated.

But some, those relating, for example, to rheumatism and gout, were more acceptable at a time when ‘orthodox medicine’ could offer no effective cure, and where remedies to alleviate pain were often in themselves harmful, and sometimes dangerous.

In this context, where the dry heat of the Victorian Turkish bath did help, the bath was already justifiably considered successful, first by hydropathists prepared to venture beyond the cold water cure dogma of Vincent Priessnitz;

In this context, where the dry heat of the Victorian Turkish bath did help, the bath was already justifiably considered successful, first by hydropathists prepared to venture beyond the cold water cure dogma of Vincent Priessnitz; second, a little later, by doctors self-confident enough not to treat the bath as yet another quack remedy threatening their livelihood.

Turkish baths are usually perceived nowadays as places for leisure and relaxation. But when introduced into the British Isles in the mid-1850s, they were, despite some recent suggestions to the contrary, predominantly seen either as therapeutic agents within hydropathic establishments or hospitals, or else as cleansing agents found in stand-alone bathing establishments, or within institutions such as workhouses, or ‘lunatic asylums’.

A final preliminary clarification: there remains much confusion generally as to what the Victorians understood by the term Turkish bath or, for that matter, what we understand by it today.

Crucially, the Victorian Turkish bath was not the Islamic hammam still found in Turkey, and wherever there are or have been Muslim communities. For bathers in a hammam wash within the hot rooms making them humid and steamy.

Nor was it the wooden banya or Russian steam bath usually experienced today in a room which is actually a prefabricated plastic shell.

There is no steam in a Victorian Turkish bath.

The Scottish diplomat David Urquhart first came across the Islamic hammam while serving in Turkey in the 1830s, later describing it in two chapters of The Pillars of Hercules.

But Urquhart was not the first to do so, and by 1850—when his book was published—the term Turkish bath was already well-established in English travel writing.

The Irish physician and hydropathist Richard Barter read Urquhart’s book in 1856 and was, as he put it, ‘electrified’ by his description of the bath.

‘On reading… [about the Turkish bath in] Mr Urquhart's The Pillars of Hercules, I was electrified; and resolved, if possible, to add that institution to my Establishment.’

Barter had already offended traditional hydropathists by installing a vapour bath at St Ann’s Hill, his hydropathic establishment near Blarney, Co. Cork. Now, he invited Urquhart to stay awhile, and asked for his help in building a ‘Turkish’ bath for his patients.

Barter believed that the therapeutic value of hot air baths increased with their temperature, and he knew that the human body can tolerate higher temperatures in dry air than in humid air or vapour.

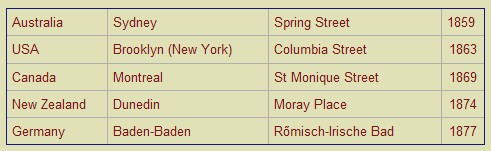

So while Urquhart remains responsible for the rapid spread of the Victorian Turkish bath throughout the British Isles and, indeed, across the Empire, Europe and the United States of America,

it was Barter, going right back to basics and following the Roman pattern, who ‘improved’ the Turkish bath and constructed the first dry hot air bath to be built in the British Isles since the Roman occupation.

It was heated by a continuous stream of hot air directed under a series of connected rooms, first the laconicum at the highest temperature, then the caldarium, and then the tepidarium, each being cooler than the previous room, with bathers spending time in each before progressing, in either direction, to the next one.

In Germany, the term, Roman-Irish bath is often preferred to Turkish bath, because it recognises the bath’s Roman origin, and its rebirth in Ireland,

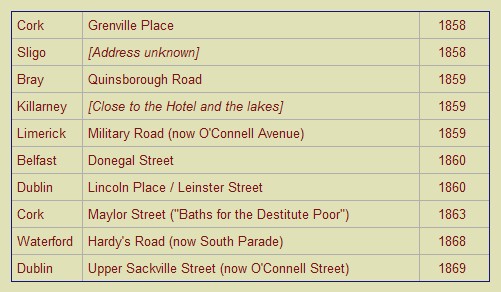

where at least ten public baths were built under Barter’s guidance, from Cork in the south to Belfast in the north.

Leeds Library & Information Service for the image of St Peter's Square baths

Peter Higginbotham for his image of Fermoy Workhouse

Pascal Meunier for his image of the Damascus hammam

The original page includes one or more

enlargeable thumbnail images.

Any enlarged images, listed and linked below, can also be printed.

Ad for the first Turkish bath in England

Before and after the bath

Booklet published by the first Turkish bath in the USA

Colney Hatch 'lunatic asylum', London

Dr Richard Barter of St Ann's, Blarney

Fermoy Union Workhouse, Co.Cork

Hot room, Al Salsila, Damascus, Syria

Newcastle-upon-Tyne Royal Infirmary

Shandon Hydropathic Establishment

St Ann's, mid-1880s

St Peter's Square, Leeds

Title page of The Pillars of Hercules

Victorian Turkish Baths: their origin, development, and gradual decline

Comments and queries are most welcome and can be sent to:

malcolm@victorianturkishbath.org

The right of Malcolm Shifrin to be identified as the author of this work

has been asserted by him

in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

© Malcolm Shifrin, 1991-2023