Amendments and revisions

It seems, unfortunately, that however carefully one attempts to check one's text, some errors—ranging from simple misprints to those which need correcting because new information is received—will inevitably remain. All such errors which come to light will be corrected on this page, and it is hoped that too much inconvenience will not have been caused to any of the book's readers—please do not hesitate to contact the author if you find any further errors, and thank you for your forbearance.

This colour is used to show the latest entries, added on 4 November 2023

| 321, 329, and 331 | Due to an unfortunate oversight, the numbering of the endnotes

to Chapters 3, 14, and 18 does not coincide with

that of the references to them in the text. In order to minimise any inconvenience this might cause to those who wish to refer to them, clicking here will lead to a correction page. This is designed to be printed as four A4 pages, with a 3cm space at the foot of each page so it can be trimmed and easily slipped into your copy of the book. |

| 42 | I am most

grateful to @JJ_Gazette who brought the 1889 Ordnance Survey map of

Dublin to my attention and who, helped by @AnFearBui, convinced me

that the map was correct and that I had misunderstood the

contemporary accounts in the Dublin Builder. This resulted

in my locating Barter's Lincoln Place Turkish Baths next to Trinity

College, rather than on the opposite side of the road. The fourth

paragraph on the page should now more correctly state: 'The new Dublin baths, opened on 2 February 1860, were in Lincoln Place. The main frontage, about 186 ft (56.7m) wide, comprised three sections, the central one slightly recessed and with an entrance porch. Adjoining this, opening off the obtuse angled pavement leading to Leinster Street, was a refreshment room and the entrance to the Turkish bath for horses and other animals, which was at the rear of the main baths.'  http://digital.ucd.ie/

http://digital.ucd.ie/ |

| 46 | Col.2; paragraph 3; last line: for '3 February' read '23 February'. |

| 62 |

For the caption to Fig 7.20, apologies are due to Dr Nebahat

Avcıoğlu whose forename has unfortunately been misspelled; In the caption to Fig 7.22, for 'Dunkerqouis' read 'Dunkerquois'. |

| 79 | Col.2; last paragraph; line 2: for 'frigidarium' read 'tepidarium'. |

| 147 | Col.2; penultimate paragraph: for 'Cookridge Road' read 'Cookridge Street'. |

| 148 |

Caption to Fig 14.10: for 'Cookridge Road' read 'Cookridge Street'. Col.2; last paragraph; line 3: The Turkish baths were delayed and did not in fact open till 21 February the following year, 1867. |

| 149 | Caption to Fig 14.11: for '1858' read '1868'. |

| 159 |

It appears that I have not been alone in incorrectly assuming that

the Ashton-under-Lyne baths (in the building known as Hugh Mason

House, Henry Square) were the baths and swimming pool Mason erected

for his tenants and workforce. Since this section of the book was written, a piece about the mill owner has appeared on the town's website, making it clear that not only did Alderman Mason not pay for the baths but, 'had in fact been a dissenter over the enormous costs of the project, and he had pointedly stayed away from the grand procession and foundation stone laying ceremony. It is ironic, therefore, that the building now bears his name.' The piece suggests that the naming decision may have been influenced by the misunderstanding over the earlier baths which had also confused me and determined that they be included in my section on philanthropy. In fact, the baths were built, 'at the public expense, at a final cost of £16,000. It had been hoped to raise money for the building by public subscription, but there were not enough people willing to start off the contributions, so the council was obliged to take out a loan to meet the costs. 'Fortunately, the land was provided by the Lord of the Manor, the Earl of Stamford and Warrington, who granted the site free of rent for perpetuity.' |

| 231 | col.1; para 3; line 3. The centigrade equivalent of 230°F should, of course, read 110°C |

| 238 |

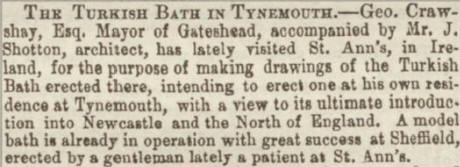

In

the book, I wrote that the first private Turkish bath in

a British house was built for George Crawshay in Tyneside. In a

lecture Why does man perspire? given in January 1861 and

reported in the Newcastle Journal, Crawshay himself claimed that

this bath was the first to be built in England

since Roman times. Four years later this was reprinted in Sir John

Fife's anthology of writings on the bath Manual of the Turkish

bath, and the claim has continued to be widely quoted. However, with the continuing expansion of the British Newspaper Archive I have been able to discover, from the 7 March 1857 issue of The Newcastle Journal, that Crawshay's bath was preceded by an earlier one, though admittedly a smaller one, built at Isaac Ironside's home in Carr Road, Walkley in Sheffield.  Ironside was the chairman of the Sheffield Foreign Affairs Committee and had also been, for a short while, the owner of The Sheffield Free Press. However, towards the end of 1856 financial problems led to the paper's being taken over by Crawshay on behalf of Urquhart. The latter was, for much of 1856, at St Ann's working with Dr Richard Barter on the first experimental Turkish bath. Ironside and Crawshay had also been there, Crawshay to see Urquhart to sort out the problems of the Free Press, and in December, Ironside, on Urquhart's recommendation, to try the bath as a cure for his recurrent boils. Both saw the ongoing work on Barter's second Turkish bath. As soon as he returned home, Ironside, a man of action, immediately called on John Maxfield (the Elder), another member of the Sheffield Foreign Affairs Committee—who would later open several commercial Turkish baths of his own—and together they built Ironside a small Turkish bath. This would have been in operation by the beginning of 1857. Like so many of those who owned private Turkish baths, Ironside was generous in welcoming visitors and sharing his enthusiasm for the bath. J W Burns, Secretary of the Sheffield FAC, and John Maxfield both wrote to the Sheffield Free Press making known his kindness. And a writer signing himself 'A subscriber to your paper' wrote that he had used Ironside's Turkish bath and since his previous visit, an unknown person had inscribed on the wall, More healing than Bethesda's pool Or famed Siloam's flood Crawshay had a much larger bath in mind and to this end took the local Newcastle architect James Shotton to St Ann's with him to see Barter's bath for himself. His bath would, therefore, have been open later in the year. Shotton then went on to build a number of other Turkish baths. |

| 243 | It was, in fact, a different Armstrong who was on the Infirmary's House Committee. Lord Armstrong's company was, however, a frequent donor to the Infirmary's funds, would have received its annual reports, and would have been well familiar with the building of the Turkish bath there, and of the beneficial results of its use with the hospital's patients. |

| 256 | The paragraph which

states that 'The high decorative standard of the two English liners,

and the facilities provided for First Class passengers…were far

superior to those on the German liner Imperator launched

three years later' could be taken to mean, as Ken Marschall has

emailed me to rightly point out, that this applied to the liners in

their entirety. But I had intended the comparison to refer only to

the Turkish baths on the liners, and the facilities within them. The wonderful swimming pool on the Imperator, for example, based on that in the Royal Automobile Club, was, of course, far superior to those on the Queen Elizabeth and Queen Mary. But the Turkish baths on the Imperator were described by John Dempsey, masseur on the ship after it was renamed Berengaria, as being 'tiled with parquet and small Italian mosaic tiles. It wasn't very bright but it was very warm.' Instead of the magnificent cooling-rooms of the Olympic and Titanic 'There were a number of cubicles with small lockers and beds on which passengers relaxed after their "treatment".' While the massage room 'was rather bland'. |

| 268 | A spurious index number, 4, has found its way into this paragraph and both it, and the endnote it references, should be ignored. |

| 281 | The author of the book Nouvelles demonstrations d’accouchemens, credited in the caption to Fig 26.5, should be Jacques-Pierre Maygrier. |

| 324 | Chapter 6 Footnote 43: the reference should be to (24 Feb 1863) p.2. |

| 335 | Chapter 24 Footnote 3: the reference should be to page 162. Chapter 25 Footnote 4: this rogue reference should be ignored |

| 346 | The forename of Davide Ritarose, great great great grandson of Charles Bartholomew, has been incorrectly spelled in the Acknowledgments, for which I apologise. |

Victorian Turkish Baths

and more about the website

Victorian Turkish Baths: their origin, development,

and gradual decline

Comments and queries are most welcome and can be sent to: malcolm@victorianturkishbath.org

The right of Malcolm Shifrin to be identified as the author of this work

has been asserted by him in accordance with the

Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

© Malcolm Shifrin, 2015-2025