This is a single frame, printer-friendly page taken from Malcolm Shifrin's website

Victorian Turkish Baths: their origin, development, and gradual decline

Visit the original page to see it in its context and with any included images or notes

5. Entrance charges and attendants' wages

Wealthier women were easily able to take Turkish baths in hotels or fashionable hydros. We know that women visited such establishments on their own because Dr Barter’s hydro, which had been served by its own railway station since 1888 (St Anne’s, on the Cork and Muskerry Light Railway) found it necessary, five years later, to add a Ladies’ Waiting Room to meet their needs.

Only rarely have I found that women and men were charged differently, even though few women had any disposable income of their own. Before 1881, the lowest charges most frequently found were 6d and 1/-; afterwards, 1/- was the most common. This was usually for the second or third class Turkish baths, but the class difference frequently meant different times of the day rather than inferior facilities or, sometimes, that the bather had to bring her own towels.

But personal cleanliness was almost impossible for those who were too poor to afford even 6d for a Turkish bath. During most of the nineteenth century, few people had their own toilets (indoors or out) and few had easily accessible running cold water, let alone hot. Additionally, there was still a tax on soap of 3d per lb which was not repealed until 1853. But the recent cholera epidemics, and the reports of Chadwick and others, were beginning to focus attention on the problems of sanitation and personal cleanliness.

It was in this context that the Ladies’ National Association for the Diffusion of Sanitary Knowledge (later the Ladies’ Sanitary Association) was founded in the Autumn of 1857 for ‘the diffusion of sanitary knowledge and the promotion of physical education among the female sex.’

It published, and widely distributed, a series of penny tracts on, for example, The worth of fresh air, The power of soap and water, and Hints to working people about personal cleanliness.

But in the mid 1860s, realising that leaflets and free bars of soap were not enough, the Cardiff Branch negotiated a deal with the local bath company whereby Turkish bath tickets issued by the association to deserving cases for a token sum, would be accepted at the Guildhall Street Baths. But it is not known for how long this scheme lasted, or whether other branches copied it.

Average entrance charges of 6d and 1/- take on a different perspective when compared with the wages of those who worked in the baths. For example, in 1891, Gloucester Corporation charged 2/- for a first-class Turkish bath, and this included a private dressing box, plunge bath, shampooing, and use of the lounge.

In the same year, at the same baths, a young woman was appointed at 12/- per week to issue tickets, and a Mrs Turner was engaged as a female shampooer,

she to attend when required and to be paid 4/- for each day she attends.

She was still there in 1921 and the Corporation presented her with a ‘purse and contents as a token of appreciation’, though we are not told the value of the contents.

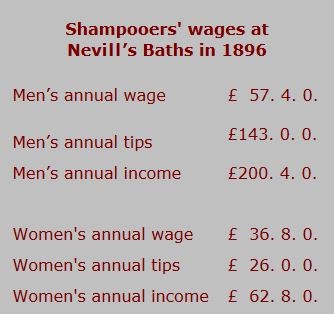

In 1896, as part of Charles Booth’s Inquiry into the Life and labour of the people in London, George Duckworth interviewed James Forder Nevill about his shampooers. At that time there were around 40 Turkish baths in London, and Nevill suggested that between them they employed around 100 male, and 20 female, shampooers.

The standard wage of a shampooer was 20/- (one pound) per week; Nevill’s paid 22/- simply to be able to say that ‘Nevills pays more than anyone else’.

But the 'standard' rate of pay did not apply to all his employees; women shampooers were paid only 14/- per week.

This page revised and reformatted 02 January 2023

The original page includes one or more

enlargeable thumbnail images.

Any enlarged images, listed and linked below, can also be printed.

Smedleys Hydropathic: main building, 1920s

Smedley's Hydropathic: Ladies Cooling room in 1920s

Massage, York Hall in the 1920s

Victorian Turkish Baths: their origin, development, and gradual decline

Comments and queries are most welcome and can be sent to:

malcolm@victorianturkishbath.org

The right of Malcolm Shifrin to be identified as the author of this work

has been asserted by him

in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

© Malcolm Shifrin, 1991-2023