This is a single frame, printer-friendly page taken from Malcolm Shifrin's website

Victorian Turkish Baths: their origin, development, and gradual decline

Visit the original page to see it in its context and with any included images or notes

2. The three Turkish baths surveyed

Two of the three establishments, Bartholomew's Leicester Square Turkish Baths and the London Hammam (the latter owned by the London & Provincial Turkish Bath Co Ltd), were visited by the same interviewer, strongly believed to be Arthur L Baxter. Although the notes, recorded on pages 2-8 of the Charles Booth Archive Notebook B161, do not give the interviewer's name, the handwriting matches Baxter's found elsewhere in the notebooks. The third establishment, Nevill's flagship baths and Head Office at 25 Northumberland Avenue, was visited by an interviewer signing himself as G.H.D. (George H Duckworth) in the same notebook (pages 9-16).

A brief note on the colours used in this article

and on the notebook transcripts

All the pages in the interviewers' notebook (from the Charles Booth Archive) are written in the same colour ink.

However, I have chosen to display each interview in a different colour so that each source is more immediately recognisable when quoted in this article. The colours used are:

BARTHOLOMEW'S; THE LONDON HAMMAM; NEVILL'S

Most of the text of the three interviews has been quoted in the remaining pages of this article, but full transcripts of the three interviews, as recorded in the notebooks, can also be read.

From one point of view, the choice of establishments was excellent, the London Hammam being the London Turkish bath, operated by a limited liability company and designed by David Urquhart, the guru of the Victorian Turkish Bath Movement. Each of the other two was part of a group. Charles Bartholomew, Foreign Affairs Committee disciple of Urquhart, owned a total of seven similar baths in various parts of England on his death in 1889, and Nevill's Turkish Baths, which operated only in London, at that time owned seven establishments of various sizes.

On the other hand, the Hammam was, as the interviewer wrote 'the most aristocratic in London' and the other two were at the middle and upper levels of the market. So it must be assumed that the conditions described in these establishments were probably better, and in some cases much better, than in the majority of smaller, less long-lived establishments. The policy and manner of running the Hammam were decided by the company's board of directors. To take just one example, the rules relating to shampooers' wages when absent from work were agreed a decade before Booth's survey, and recorded in the company minute book in December 1885.

In 1896, the year of these interviews, there were at least 36 Turkish baths in London, so that three establishments is a small sample, and a modern survey would doubtless wish to include some of the more modest, less expensive establishments to get a more balanced view.

It is a pity also, though no fault of Booth, that local authorities in London falsely believed they were not allowed to open Turkish baths, so that none was opened before Camberwell's in 1905. No comparison can be made, therefore, between conditions in privately owned baths and those in publicly funded facilities. But they were quicker in the provinces: we know, for example, the wages of some of the staff at the Barton Street Turkish Baths in Gloucester, and these will be discussed briefly in due course, below.

Bartholomew's Turkish Bath, 23 Leicester Square

When Charles Bartholomew died in 1889 he also owned Turkish baths in Bristol, Manchester, Worcester, Birmingham, Bath, and Eastbourne. Though he had children of his own, he left all his establishments to Bassalissa Harriet Herriott, daughter of William Mosdell Herriott who had himself owned two Turkish baths in Manchester. Apart from the establishment in Bath (which she gave to Bartholomew's niece, Kate), Bassalissa sold all the remaining baths except this one. At some stage, she had married a Mr Kenny, who was then, or perhaps later became, the Manager. Mr E D Kenny (sometimes elsewhere spelled Kenney) was interviewed on 20 April 1896.

When Charles Bartholomew died in 1889 he also owned Turkish baths in Bristol, Manchester, Worcester, Birmingham, Bath, and Eastbourne. Though he had children of his own, he left all his establishments to Bassalissa Harriet Herriott, daughter of William Mosdell Herriott who had himself owned two Turkish baths in Manchester. Apart from the establishment in Bath (which she gave to Bartholomew's niece, Kate), Bassalissa sold all the remaining baths except this one. At some stage, she had married a Mr Kenny, who was then, or perhaps later became, the Manager. Mr E D Kenny (sometimes elsewhere spelled Kenney) was interviewed on 20 April 1896.

The London Hammam, 76 Jermyn Street

The same interviewer

visited the Hammam on 22 April 1896. Although he refers to James Waugh as Manager of the Hammam, his rôle was different from that of Mr Kenny in Leicester Square. Waugh had joined the London & Provincial Turkish Bath Co in 1870 as a 39 year old temporary Company Secretary, and he was to remain its secretary until 1907. The manager's functions would have been undertaken at the Hammam by a Superintendent, a Foreman Shampooer, and a Housekeeper.

The same interviewer

visited the Hammam on 22 April 1896. Although he refers to James Waugh as Manager of the Hammam, his rôle was different from that of Mr Kenny in Leicester Square. Waugh had joined the London & Provincial Turkish Bath Co in 1870 as a 39 year old temporary Company Secretary, and he was to remain its secretary until 1907. The manager's functions would have been undertaken at the Hammam by a Superintendent, a Foreman Shampooer, and a Housekeeper.

From Urquhart's day onward, the company had a caring attitude to its staff, though this did not always prevent shampooers from breaking the company's rules about tipping. There had been trouble on this score some three years earlier due in the main to the Hammam going through a particularly bad patch with a consequent diminution in the amount of bathers' tips.

The interviewer notes Waugh's frank comment that,

The Hammam has not been so prosperous of late years as when first started partly owing to the increase of Baths in London, but still more from the fact that people go out of town so much more than they used to, especially on Saturday and Sunday.

But he omitted to mention that the level of service and cleanliness had fallen during the previous few years after the deaths of several of the original directors.

Nevill's Turkish Baths, 25 Northumberland Avenue

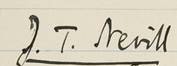

Interviewer G.H.D [George H Duckworth] visited Nevill's on 23 April 1896 where [he maintains that] he spoke with D. T. Nevill, the Turkish Bath Proprietor. In this he was mistaken for the only two proprietors at that time were James Forder Neville and Henry Neville (a barrister). It seems most likely, therefore, that the interview was with a knowingly successful James Forder Nevill. In his effort to get down his all his interviewee's words, Duckworth incorrectly noted the speaker's forenames. These can be seen here, as they appear in the notebooks, and seem, to me at least, to be J T.

Interviewer G.H.D [George H Duckworth] visited Nevill's on 23 April 1896 where [he maintains that] he spoke with D. T. Nevill, the Turkish Bath Proprietor. In this he was mistaken for the only two proprietors at that time were James Forder Neville and Henry Neville (a barrister). It seems most likely, therefore, that the interview was with a knowingly successful James Forder Nevill. In his effort to get down his all his interviewee's words, Duckworth incorrectly noted the speaker's forenames. These can be seen here, as they appear in the notebooks, and seem, to me at least, to be J T.

But this interview was an important one and we learn from Neville far more about the general state of Turkish baths in London at that time than from either of the other two interviewees.

The interviewer reports not only the factual answers to his questions but also reports all his many asides as, for example, his remarks on shampooers' drinking habits:

Shampooers still have a name for drink. All take a large quantity of beer. Thirsty work. But drunkenness is less common than it was. He sacks a drunk man at once. … Customers are less willing now than formerly to be shampooed by a drunkard.

and that he has a cynical view of the claims of Turkish bath proprietors for,

Every bath he knows is called

1. The Largest

2. The best ventilated

3. The most luxurious

He suggests that there were less than '100 male shampooers in London & 12 wd cover the Female shampooers' and notes the existence of a related professional, the masseuse.

There are a good many masseuses; about 20 I wd say round about Piccadilly. Has never been to one but many of his customers have spoken to him about them from experience. Customers who have gone in expecting medical treatment [?] are put in a bath & then electricity is applied by the masseuse. Most of them he hears are procuresses, They have sleeping rooms upstairs. It is a new form of the business & has not been in vogue for more than two or 3 years. Probably the police could give a good deal of information about them.

Throughout the survey, interviewers also tried to speak with appropriate trade union representatives, but here there was none to be found.

There used to be a Trade Society. He thinks it has been dead for 3 or 4 years. The organ of the Shampooers Society is a small Islington local paper with offices within 100 yds of the Angel. Called the ‘Islington Gazette’. He was at daggers drawn with the Soc when it did exist.

Nevill's reference is to the short-lived Turkish Bath Attendant Mutual Aid Association. His mention of 'The organ of the Shampooers Society' is the derogatory remark of one who admits to have been 'at daggers drawn' with the association and refers only to reports of its meetings published in issues of The Islington Gazette, a local paper which continues to serve its readers in the borough of Islington.

Neville was clearly not one of many proprietors who worked well with the association, especially with regard to the impending legislation on shop opening hours.

This page slightly revised 09 February 2023

Indy Bhullar Library Enquiries, LSE Library, for help with the Nevill interview

The original page includes one or more

enlargeable thumbnail images.

Any enlarged images, listed and linked below, can also be printed.

Rules governing shampooers' absences

Victorian Turkish Baths: their origin, development, and gradual decline

Comments and queries are most welcome and can be sent to:

malcolm@victorianturkishbath.org

The right of Malcolm Shifrin to be identified as the author of this work

has been asserted by him

in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

© Malcolm Shifrin, 1991-2023