Nothing but a load of hot air:

some problems, conflicts, and controversies

arising during the development

of the Victorian Turkish bath

This is a single frame, printer-friendly page taken from Malcolm Shifrin's website

Victorian Turkish Baths: their origin, development, and gradual decline

Visit the original page to see it in its context and with any included images or notes

5. Attitudinal issues: doctors' attitudes

What set the cat among the 19th century pigeons was that from the beginning the Turkish bath was also promoted as a therapeutic agent. Urquhart originally became a convert as a result of its beneficial effect on the neuralgia from which he suffered for most of his life. Other sufferers found the bath helped significantly to relieve the pain of, for example, gout and rheumatism, where no cures were then available.

While the Turkish bath should have been acceptable as a therapy in the hands of Dr Barter, it has to be remembered that doctor he may have been, but his primary approach was through hydropathy, the cold water cure, thought by many doctors to be just another form of quackery.

And, at first, Barter was also criticised by his fellow hydropathists, for whom, as disciples of Vincent Priessnitz, bathing in hot air instead of wet sheet packing was anathema. But Barter’s patients found the Turkish bath less rigorous and more enjoyable, and other hydropathists soon followed suit in order to stay in business. Medical practitioners were by no means fully professionalised in the mid 1850s and many, if not most, ordinary doctors, were against the bath from the start. At first glance it might seem the doctors had a good case. A display advertisement for the very first Turkish bath in England included a paragraph which claimed that,

It fortifies the body against colds, influenza, consumption, gout, rheumatism, nervousness, neuralgia, tic-doloureux, tooth ache, all skin diseases, and disorders arising from the liver.

while the following paragraph asserted that,

The right use of it will cure any of the above diseases.

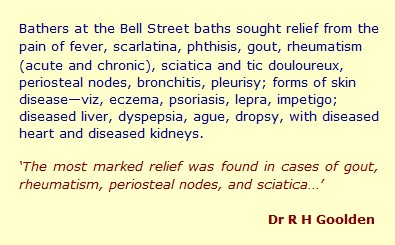

But the doctors’ objections were subjective, and it was not until the first bath opened in London in 1860 that the matter began to be discussed more objectively. R H Goolden, a doctor at St Thomas’s Hospital who was campaigning to instal a Turkish bath there, visited the first London bath in Bell Street and wrote to The Lancet to say that invalids there had been quite happy to talk about their complaints, which he listed.

He continued:

To expect a cure, or even benefit, in all these cases, would be unreasonable; but I found relief produced to a far greater extent than I was prepared for.

In an editorial in the same issue, The Lancet called for some unbiased research, with the involvement of the hospitals, to discover,

how the air bath operates on the human organism. If any, what is the nature of the danger to be apprehended, when a healthy body is the subject? What is the kind of relief produced in disease? What are the constitutional or pathological peculiarities that are injuriously influenced?

But while some correspondence followed, no significant research was undertaken and prejudice continued. Nearly twenty years later, Dr Andrew Clarke wrote,

As I think that the Turkish Bath should not be used without the sanction of a medical man, I am unable to give my support to any project for its indiscriminate and unguarded use.

and this was echoed by many others:

Dr Elizabeth Blackwell begs to state, respecting the propriety of introducing the Turkish bath into the proposed baths for the working classes [in Paddington], that she has known so much mischief arising from the ignorant or careless use of that powerful agent, the Turkish bath, that she does not consider it a safe appliance for ordinary public baths.

Some doctors forbade their patients to use Turkish baths. From the opening of the first baths until the middle of the twentieth century, proprietors had to fight back with a stream of advertisements, publicity brochures, and even books.

Five objections, which may have reflected the contraindications bathers were given by their doctors, were refuted repeatedly in publication after publication. These were: that the Turkish bath was injurious to the blood; that bathers are likely to catch a cold when leaving the heat of the bath; that the Turkish bath should be avoided by those with a weak heart; that the Turkish bath is weakening and enervating; and that the Turkish bath should not be taken by the elderly.

This page revised and reformatted 02 January 2023

The original page includes one or more

enlargeable thumbnail images.

Any enlarged images, listed and linked below, can also be printed.

Rheumatism and its treatment by Turkish baths

Caricature: I am inclined to knock these fellows down…

Before and after the Turkish bath (part of an ad)

Victorian Turkish Baths: their origin, development, and gradual decline

Comments and queries are most welcome and can be sent to:

malcolm@victorianturkishbath.org

The right of Malcolm Shifrin to be identified as the author of this work

has been asserted by him

in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

© Malcolm Shifrin, 1991-2023