Clean in body and mind:

David Urquhart’s Foreign Affairs Committees

and the Victorian Turkish Bath Movement

This is a single frame, printer-friendly page taken from Malcolm Shifrin's website

Victorian Turkish Baths: their origin, development, and gradual decline

Visit the original page to see it in its context and with any included images or notes

3: The committees and the Free Press papers

But while Urquhart was delighted that at last progress on building a Turkish bath was being made, he was also, with his wife Harriet, heavily involved with his political work.

Neither the end of his diplomatic career, nor an unsatisfactory period as MP for Stafford, had dimmed his interest in foreign policy, or diminished his view of what he had to offer his country.

In the early 1850s, the growing hostility between Russia and Turkey, which was to lead to the Crimean War, encouraged him to create a series of political pressure groups, starting in Newcastle-upon-Tyne.

Soon, these Foreign Affairs Committees were also to be found in Preston and Manchester, and nearly thirty could be found in Yorkshire alone.

At their peak, there were well over one hundred of them, though many comprised just a handful of members. But, surprisingly, his support was increasingly coming from ordinary working-men.

The time he spent at Blarney in 1856 was, therefore, not only the most promising for the development of the Turkish bath, but was also the period of greatest activity of the Foreign Affairs Committees which were, as Asa Briggs put it, 'not so much a cohesive movement as a series of bouts of agitation'.

A year earlier, in April 1855, the very atypical secretary of the Sheffield Foreign Affairs Committee, Isaac Ironside, a wealthy, radical local councillor, bought himself a local newspaper, The Sheffield Free Press.

Starting with regular coverage of the Sheffield committee’s meetings, it developed over the following months into what was, in effect, the mouthpiece of Urquhart’s movement.

Since Urquhart himself contributed much of the political input, the editor was not too surprised to receive an article on Turkish bath at Blarney, signed ‘Caritas’, Harriet Urquhart’s pseudonym when writing political articles for the Morning Advertiser.

And two months later, on 21 June 1856, two unusual and very different articles, appeared. One was the first of a series called Revelations of the diplomatic history of the eighteenth century by a writer signing himself Dr Karl Marx and the second, presumably aimed at the same readership, was an anonymous article headed Introduction of the Turkish bath into Ireland describing the laying of the foundation stone for a new, larger Turkish bath at St Ann’s.

A month later, an article entitled Introduction of the Turkish bath into our towns and cities appeared. Its author wrote:

There appears promise of a 'movement' in favour of water and cleanliness; and it would not be astonishing if Turkish Baths became the rage, and succeeded the small bonnets and coloured shirts.

Soon a shorter version of the paper, omitting purely local news, was published simultaneously in London as The Free Press.

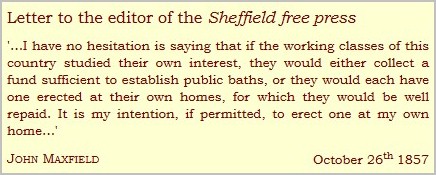

For some months, both papers continued with this mix of foreign affairs and Turkish baths, though the Sheffield paper ceased publication at the end of 1857.

Some questioned the connection between foreign affairs and the bath.

Some surprise has been expressed that we should make mention of the bath in a political journal. That such objections should be made is a proof that the subject is not understood and requires to be pressed upon public attention…

It is not only a remedy and preventative of disease, a sweetener of the temper and a promoter of thorough cleanliness, but it is an antidote to intemperance and a means of destroying the barriers which now separate entirely the lower from the higher classes.

No barrier of ceremony, of pride, or of habit, is so great as that of filth which, in these times, especially in large towns, separates the poor from the rich, as if they were not members of the same state, but, as Disraeli has phrased it, 'the two nations.'

Many of the articles and news items inspired committee members to write about their own aspirations.

After reading about the party Urquhart gave for workers building the new Turkish bath at St Ann’s, Charles Bartholomew, secretary of the Bristol Foreign Affairs Committee, wrote telling him that he intended to build a Turkish bath in Bristol.

…The First thing I have done to impress upon the minds of a number of intelligent Working men the nicissety of at once introducing it into our City before our Condition get any worse.

Then Sir us Working Men Sum of us Masons, Carpenters Glazers & Smiths. We will set to work nights till its completed. I shall if possible get the Committee to do it so after wards it may be its property.

Bartholomew was unsuccessful on this occasion but, four years later, he did open a Turkish bath in Bristol, the first of seven which he owned on his death, in 1889, at the age of 59.

This son of an impoverished farm labourer became a gifted publicist for the Turkish bath movement.

He lectured, wrote pamphlets, advised Borough Councils on how to construct their own Turkish baths.

And named one of his sons Urquhart in gratitude.

Like most of the committeemen, Bartholomew was barely educated, yet highly intelligent. Urquhart chose carefully those whom he wished to run his committees, and trained them intensively in reading and understanding abstruse government Blue Papers and diplomatic treaties, in public speaking and logical thinking, in organising meetings, in writing letters to newspapers and their members of Parliament—and, tellingly, in the use of Socratic dialogue as a method of converting an opponent.

This page revised and reformatted 02 January 2023

The original page includes one or more

enlargeable thumbnail images.

Any enlarged images, listed and linked below, can also be printed.

Bartholomew's Turkish Baths in Bristol

Victorian Turkish Baths: their origin, development, and gradual decline

Comments and queries are most welcome and can be sent to:

malcolm@victorianturkishbath.org

The right of Malcolm Shifrin to be identified as the author of this work

has been asserted by him

in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

© Malcolm Shifrin, 1991-2023