'Semi-success' in London:

David Urquhart, the London Hammam, and

the London & Provincial Turkish Bath Co Ltd

This is a single frame, printer-friendly page taken from Malcolm Shifrin's website

Victorian Turkish Baths: their origin, development, and gradual decline

Visit the original page to see it in its context and with any included images or notes

3: The class barrier

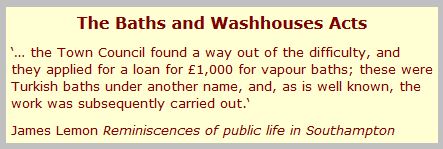

Some local authorities outside London did install a Turkish bath. Southampton Corporation, for example, waited till 1894—and then pretended that it was a vapour bath.

But Bradford Corporation just took a chance and installed one as early as 1867. John Howarth, superintendent at Bradford, was in no doubt about its value:

As a cleansing agent, pure and simple, there is no comparison between the Turkish and the ordinary warm bath; because a person may take a warm bath and still not be clean, as may be proved by his taking a Turkish Bath immediately afterwards.

Such statements were often resented. Dr Christopher Samuel Jeaffreson, an advocate of the bath, told the BMA:

It is somewhat repugnant to the English notion to be told that we are a dirty set of fellows; that our baths, our sponges, our soap, and flannels, only increase our filth by rubbing the dirt in; and that cleanliness can only be obtained, not ‘by the sweat of our brows’ only, but that we must be washed from within outwards by myriads of rippling streams of perspiration.

To no avail did Richard Metcalfe propose that Paddington Vestry provide Turkish baths for the working class because air was more plentiful than clean water and cheaper to heat, and that more people could more economically progress through a Turkish bath than could occupy separately partitioned warm water baths, which had to be emptied, cleaned and filled afresh for each bather.

So, for nearly 50 years, until 1905 (when Camberwell Borough Council opened its Old Kent Road Baths) the provision of cheap Turkish baths for London’s poor was constrained by the need of private establishments to make a profit.

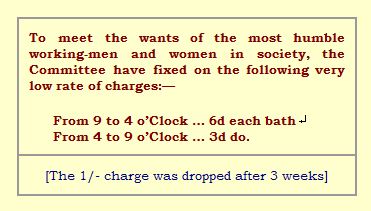

Though not required by law to do so, most felt it necessary to provide different classes of baths. The Leeds Road Turkish bath, opened by the Bradford foreign affairs committee as early as December 1857, felt compelled to charge three different rates (1s., 6d, and 3d).

Nevertheless, as true disciples of Urquhart, they emphasised in their first advertisements that,

The Turkish Bath is known to be much needed by all classes,—is one of the best means for promoting sanatory well-being, and they have fixed the Charges at so very low a rate as to meet the wants of all.

Persons bathing between the hours of FOUR to NINE in the evening at a charge of THREEPENCE have all the privileges of those paying the highest price in the morning.

In practice, of course, this separated bathers no less than if they had advertised three separate classes of bath.

The co-operative baths in Rochdale were opened in 1859 at a cost of £200, raised by working men in 1/- shares. But even here there were three classes of bather at 2/-, 1/-, and 6d.

Urquhart had seen people of all classes mixing freely in the baths of Constantinople. Putting his ideals into practice, he made the Turkish bath at Riverside, his Rickmansworth home, freely available to any invalid who approached him.

Class was irrelevant to him and, in politics also, he helped all who were serious in intent. He had, according to Lord Morley,

a singular genius for impressing his opinions upon all sorts of men, from aristocratic dandies down to the grinders of Sheffield and the cobblers of Stafford…

In 1856 he had written in The Free Press that the Turkish bath was, ‘a means of destroying the barriers which now separate entirely the lower from the higher classes’. He continued:

No barrier of ceremony, of pride, or of habit, is so great as that of filth which, in these times, especially in large towns, separates the poor from the rich, as if they were not members of the same state, but, as Disraeli has phrased it, ‘the two nations’.

In truth, there was no way that Turkish baths at 2d each could be made to cover their costs, especially with the price of coal fluctuating over the years.

This page revised and reformatted 02 January 2023

The original page includes one or more

enlargeable thumbnail images.

Any enlarged images, listed and linked below, can also be printed.

Betowelled patron of the London Hammam

The West Bowling District Baths, Manchester Road, Bradford

Estimates of the cost of bathing 1,000 people

Kidderminster Baths, Mill Lane

Shampooing room, Camberwell Baths, 1905

Cooling-room at Glossop Road, Sheffield

Urquhart's Riverside Turkish bath, near Rickmansworth

Victorian Turkish Baths: their origin, development, and gradual decline

Comments and queries are most welcome and can be sent to:

malcolm@victorianturkishbath.org

The right of Malcolm Shifrin to be identified as the author of this work

has been asserted by him

in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

© Malcolm Shifrin, 1991-2023